It’s a hard world for us Pagans to relate to. The most popular usage for the word ‘myth’ is ‘a widely held but false belief or idea ‘. We generally speak of the religious beliefs of ancient Pagans as being ‘myths’, but what does this really mean for us? How do we actually relate to myths, from our own culture or others?

There seems to have been a shift in language usage such that the word ‘mythology’, which ought to mean ‘study of myth’ or more literally, ‘talking about myth’ has become equivalent to ‘myth’ itself. Google certainly indicates this. A search for ‘myth image’ produces masses like these arrows, not a deity in sight. Whereas, a search for ‘mythology image’ gets you Zeus and other  Olympians, Thor and his hammer, and lots more. As for ‘mythos’, that seems to be a brand of beer! Whether a source uses ‘myth’ or ‘mythology’ is itself an interesting point. I do find that the better writers tend to use the former term, whilst the potboilers and plagiarists use the latter. If one looks in a bookshop or library for ‘mythology’, it’s almost all to be found in the “children’s section”. Victorian academics had the notion that the people in traditional cultures have ‘primitive’ and ‘undeveloped’ minds, supposedly analogous to those of children. Hence myth was and is thought only suitable for children (once stripped of all sex and much of the violence), irrelevant to adults.

Olympians, Thor and his hammer, and lots more. As for ‘mythos’, that seems to be a brand of beer! Whether a source uses ‘myth’ or ‘mythology’ is itself an interesting point. I do find that the better writers tend to use the former term, whilst the potboilers and plagiarists use the latter. If one looks in a bookshop or library for ‘mythology’, it’s almost all to be found in the “children’s section”. Victorian academics had the notion that the people in traditional cultures have ‘primitive’ and ‘undeveloped’ minds, supposedly analogous to those of children. Hence myth was and is thought only suitable for children (once stripped of all sex and much of the violence), irrelevant to adults.

There is for me something a little strange about this ‘mythology’ word – although similar dual usage has happened also with some other ‘ologies’. To me ‘mythology’ also suggests a ‘subtext’ – specifically that what is being studied is only the ‘myths’ and not that to which they refer (the deities). In other words, it is fundamental to most presentations of ‘mythology’ that the deities do not actually exist – and so they cannot in themselves be a valid target of study. Only what people have said (and especially written) about them can then be of concern. Hence the title of this piece – it is ‘talking about’ those who ‘talk about myth’

Really though, that’s not my interest – since for us as Pagans, it seems to me that the point of mythology must be to know better the nature of God/dess/e/s themselves. Arguably better for us to drop the term ‘mythology’ and instead use ‘theology’ (study of the ‘theioi’ ) or the feminist term ‘thealogy’.

It’s certainly not an easy task to relate to Myth at all. For us as NeoPagans, embedded in the ‘western’ commodity-culture, our mythic heritage has been perverted and largely destroyed. We can speculate as to how patriarchal cults have rewritten older myths, typically rendering the results incomprehensible, but though we might try a ‘re-inversion’ it’s not easy to recapture the ‘originals’. Many scholars tell us that no such originals ever existed. They tend to prefer texts to oral tradition, even though writing is a fairly recent event in human experience.

Clearly we ‘moderns’ have a real problem between Myth and Science. Rationalists tell us that myth is just ‘bad science’, and so superseded. We can disagree, and say that myth is the expression of spiritual vision. But how many of us could seriously speak of our galaxy, the word itself derived from Greek for ‘milk’, still known as the Milky Way, as drops from the breasts of the Great Mother?

In ancient Greece, the term used for stories about the ‘Gods’ was “mythos”, which means little more than just ‘story’. This word was often used in association partly with ‘logos’, which has connotations of order and knowledge – logos being the logic behind an argument. Intriguingly, the writer Hesiod (not usually my favourite) makes a deeply-felt contrast between the two. For him, mythos was truth and logos was lies,’seductive falsehoods’. One might speculate that this rather grumpy character had had a bad experience with lawyers… I find his opposition amusing anyway, especially when I bear in mind the the Christian ‘message’ is – in the ‘Gospel of John’ anyway – specifically referred to as ‘Logos’ (usually translated as ‘the Word’ in English). I think Hesiod would be even more unhappy with the ‘logos’ of public discourse nowadays – faced with the barrage of advertising, political propaganda and fake news in general, he would rather talk to his sheep!

If you search for ‘definitions’ of ‘myth’ alongside ‘legend’ and related words, you will find a clearly-graded ranking. Myth is reserved for deities, especially stories of ‘creation’ (effectively, ‘bad science’) whilst ‘legend’ is considered to relate events concerning humans (effectively, ‘bad history’). The bottom ranks of the hierarchy are fable, folk tale and ‘fairy tale’ – all suitable only for the ‘common people’ and to fill the heads of children. But this is a construction of our culture’s intellectuals – people in traditional Pagan cultures, past and present, do not endorse any such separation.

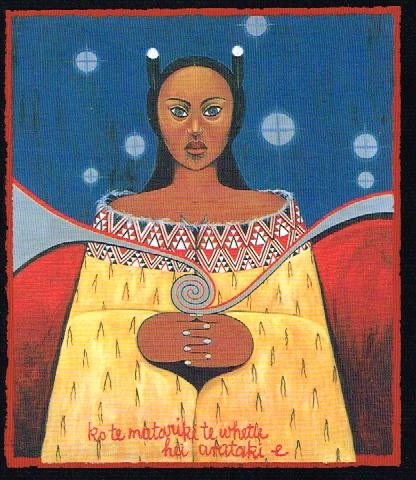

Over the past decade or so I’ve visited family in Aotearoa / New Zealand several times. There’s plenty of opportunity to enjoy a ‘Maori Cultural Heritage Experience’ but very little chance for Pakeha tourists to talk with any Maori about real spirituality. Whilst their faith has certainly ‘survived’, it does seem that to an extent there is an active process of rediscovery underway. A pride in traditional culture and festivals links closely to spirituality. For example, the Maori festival of Matariki marks the heliacal rising of the Pleiades, a little before the winter solstice. Increasingly this is celebrated as a public holiday, but the connections to spirituality are taken seriously (unlike Xmas).

In Maori, ‘Mata-ariki’ means “the eyes of god”. According to myth, when Ranginui, the sky father, and Papatūānuku, the earth mother, were separated by their children, the god of the winds, Tāwhirimātea, became so angry that he tore out his eyes and threw them into the heavens. Others say Matariki is the mother surrounded by her six daughters, Tupu-ā-nuku, Tupu-ā-rangi, Waitī, Waitā, Waipuna-ā-rangi and Ururangi. Another account explains that Matariki and her daughters appear to assist the sun, Te Rā, whose winter journey from the north has left him weakened.

You may have read , in works by writers such as Eliade, how in traditional spirituality, myth is of fundamental importance. Every single act, the outwardly ordinary as well as those of magic and ritual, takes on a sacred character precisely as it re-enacts the primal events of the myth. Furthermore, each such re-enactment is understood as a re-creation of whatever the primal events brought into being. Now, it’s one thing for an academic to say this sort of thing, far removed from its actual substance – it’s quite another when a modern writer speaks of their own tradition in very similar language.

I was fortunate to purchase a copy of ‘Tohunga’ by Samuel Timoti Robinson (it’s often difficult to locate a source for this book). Whereas almost all accounts of indigenous myth have been collected by hostile redactors – missionaries or colonial administrators – this is by a modern practitioner initiated into the Maori shamanic / priestly tradition. The first quarter of Robinson’s book presents Maori myth from ‘before creation’ – the Ages of Void and Night – to the population of the world by our ancestors. Robinson’s account has great depth and complexity – far beyond the ‘just-so-story’ material one usually encounters. One feels then that other oral traditions have no less substance.

The second degree (of seven) in tohunga training is specifically focused on learning systematically the lore of the many deities and prayers. Speaking of ‘karakia’ (prayers of power) Robinson writes (my brackets):

The karakia …called upon the aid of atua (deities) …for hunting…gathering food…calling and quelling the winds and rain, chanting while weaving so as to hold the fibres together…every aspect of Maori daily life.”

The tohunga ascends the macrocosm by karakia and contacts the higher powers by naming the atua…then, when we apply this karakia to the physical level, such as when calling Rangi to bless a child, these heavenly powers are brought down to out level in Te Ao Marama.”

The names of the wairua (spirits) become the power bases by which rituals are empowered.

To join the karakia to Hawaiki (the mythical origin place) has the added mana of the source…instead of our individual power the Maori has the power of everyone before him in his whakapapa.

In the NeoPagan movement we don’t really have a lot of myth. The myth of Atlantis has been superseded, I think, by the science of plate tectonics and continental drift. (So Atlantis was ‘bad science’, though to credit Blavatsky et al, it was not until nearly a hundred years later that the modern theory was accepted.) The Wiccan second degree employs a much-questioned ‘Descent of the Goddess’ myth – usually considered to have written by Gardner himself.

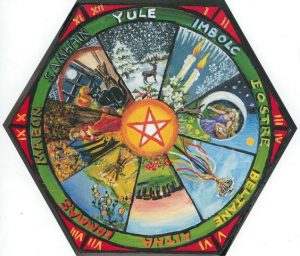

Most popular, surely, is still the Wiccan ‘Wheel of the Year’ myth, in which their Goddess and God are directly embodied in the changing of the seasons. This is mostly derived from the ‘Golden Bough’ by James Frazer and the ‘White Goddess’ by Robert Graves. Various ideas of twin gods in conflict are mixed in, not always very consistently. I suspect though, that whilst most Pagans think it’s important to be in tune with the physical cycle of the year, as well as with its underlying spiritual currents (which of course differ greatly in different climates. and reverse in the southern hemisphere), nonetheless they don’t feel a need to mythify this especially. Nor can it have been so significant to the first generation of Wiccans, some of whom have suggested that ‘doing magic’ was of more importance than celebrating festivals. Starhawk’s ‘The Spiral Dance’ presents the creation myth from the Feri tradition, but as far as I am aware, that title is the only popular Wiccan book with its own ‘mythic’ narrative.

One of the major changes in the Pagan community during my 40+ years has been the shift away from duotheism to polytheism in general, and to specific polytheisms, such as Hellenismos or Kemeticism, as well as various Celtic and Norse reconstructions. Barely a handful of us will have born into polytheism, so these commitments are the result of explicit choice – however much we feel the Gods have directed us. I’m wondering how much this movement derived from a ‘need for myth’, unsatisfied by Wiccan or not-very-theist-Druid Paganism, and to how great an extent myth is the centre of the spiritual practice, rather than a background. (I would love to hear more from practitioners in these faiths.) Certainly I’m aware of a distinct divergence in the Heathen community, between those who treat the Eddas as ‘authoritative sacred texts’, not so unlike the Abrahamics, and those of more flexible views. (You might be interested to know that if you’re a prisoner in the UK, you can get a free copy of the Eddas, just like the Bible and the Koran, but these is the only Pagan text given such status.)

Looking at some of the Pagan faiths that have maintained continuity – the many Hindu traditions, say, or Shinto, it’s not always easy, when we are not fluent in the relevant language, for us to know whether myth is a fundamental part of daily spiritual practice, or more the excuse for a public festival. In Voudoun, the loa are considered immediately present at every event, so perhaps in that religion myth plays a lesser part.

Many of us are deeply unsatisfied by standard versions of myths – taking the view that what has come down to us is not much representative of ancient spirituality, having been heavily ‘patriarchalised’ and otherwise amended by those with political and economic power. You can find many writers describing this – a classic is ‘The Paradise Papers’ by Merlin Stone. But if we are to do more than grumble, and instead regain ‘true myth’ we will have to write it ourselves. If there ever were texts of these ‘tru myths’, all have gone to the fires. So rather than sneering at ‘Unverified Personal Gnosis’ (UPG) we have to ask the deities to tell us their stories directly. Better if we don’t expect all such gnosis to be consistent! We won’t all like everyone else’s visions.

The process is happening. One of my great favourites is Charlene Spretnak’s “Lost Goddesses of Early Greece”. Another good place to rummage is at Bibliotheca Alexandrina where the folks have produced a number of ‘devotional anthologies’, often including retellings as well as modern prayers.

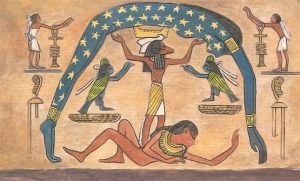

Creation myths have not much featured as yet. It’s notable that the Abrahamic cults make a big deal of these. Victorian-era scholars, whose influence continues, tended to interpret Creation as making a Creator automatically ‘Top God’. Then writers like Eliade describe how these deities seem to move off the scene, using the term ‘deus otiosus’. I am inclined to think that this is a deep misunderstanding of Pagan Creation Myth. I would suggest that our myths are conceptually quite different from the Abrahamic stuff. More precisely, rather than their separation of Creator and Created, in the Pagan myths the Pagan Creator deities are the Creation Process. In Robinson’s book mentioned above, creation is termed ‘Te Wananaga o Te Ao Marama’ – the coming of our world of light. The language is deep and subtle – it’s not like making a cake, or anything else in which creator, source material and created result are identifiably separate.

For myself, I felt the ‘craving for true myth’ some years back. Writing for the readers of ‘The Pipes of PAN’ magazine, I initiated a ‘competition’ to encourage ‘new’ myths of creation. The prize was awarded to the poet Hilary Llewellyn-Williams for her story “Spinning Woman”. I didn’t write at that time, but more recently found ‘The Drummer’ was speaking to me. The story She gave combines a Creation myth with a very specific aetiology (origin story).

Just because they are deities, doesn’t mean they don’t have a sense of humour…

You can find the Drummer’s story here: https://pandorasjar.org/the-drummer-the-stones-and-the-bunnies