https://www.amazon.co.uk/Naming-Goddess-Trevor-Greenfield/dp/178279476X/

You’ve all heard of Pandora. You’ve all been told the story of the silly girl whose curiosity released all the ills of the world. She has the distinction of being the second-most-blasphemed Goddess in human history – after Eve, Mother of All Living. Perhaps now that hardly anyone actually believes in ‘Eve’, Pandora is tops!

I wrote rather more briefly about Pandora in the collection ‘Naming the Goddess’ ed. Trevor Greenfield, Moon Books 2014. Some new insights have arrived since then.

Pandora never had a ‘box’ – the 16th-century writer Erasmus mistranslated the Greek word ‘pithos’ (a large storage jar) as if it had been ‘pyxis’ (box). The story was somewhat confused with that of Psyche (the story within a story in Lucius Apuleius wonderful ‘The Golden Ass’). Just about every artist since then has reproduced the mistake – lovely pictures but not much help when it comes to understanding Her. Except maybe that the word ‘box’ is sometimes used as a euphemism for female organs…This has been a very sticky error – one even finds Goddess-worshiping Pagan writers caught up in it.

This painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti is pretty much standard – tells us more about the artist’s relationship to the model (Jane Burden Morris) than about Pandora.

In my local ‘high street’ Pandora has been turned into a shop selling expensive bling – no doubt in costly ‘boxes’. Just as the name of our Goddess Isis has been hijacked of late, so a google for Pandora now prioritises shopping. And just about every hack journalist in search of a cliché will open up “Pandora’s Box” before long. Computer games pervert Her into a ‘goddess of calamity’ and deceit. There are countless novels using Her name – Amazon currently has no less than 6809 results for her – varying from bonkbuster and soft porn to a rather nice children’s book by Victoria Turnbull, in which Pandora is a fox in a dress.

A more appropriate recent tribute is that Her name is used for the ‘idyllic’ planet portrayed in the 2009 film ‘Avatar’. The beautiful inhabitants live in harmony with nature and worship a mother-goddess named Eywa. I feel very uncertain as to the ‘message’ of this film – can’t help feeling that a subtext is the impossibility of such life for we humans.

The usual tale derives from the 7th-century bce Hesiod whose works could be considered the ‘party line’ of ‘Greek mythology’. I don’t believe that we should think of these stories as ‘myths’ – at least if we equate the word ‘myth with ancient Pagan religion – but rather as ‘just-so stories’, that is, something ‘deliberately made-up’. Hesiod’s material is reproduced without question by most writers today, as if it were definitive. However, anyone attempting a serious study of ancient Greek religion must soon realise that things were vastly more complex. The Hesiod story of Pandora has a substantial presence in our culture, which one could even describe as obsessive, but ancient Greeks seem to have largely ignored it, as did most Roman mythographers. Other writers, Theognis for example (and also Aesop) told a quite different story in which a Jar of Blessings was given by Zeus to humankind (or ‘man’ – sic) but that a man (so not Pandora) opened it, and all but Hope skipped off back to heaven!

The similarity of the stories of Pandora and Eve is deeply suspicious. Both are ‘first women’, both are made of clay (Eve indirectly, after Adam), both are given responsibility for the presence of evil in the world. Early Christian writers saw this clearly and John Milton made the connection in his ‘Paradise Lost’ some 350 years ago, but all these would have thought the Eve story as written millennia before that of Pandora. The early feminist Mary Wolstonecraft recognised clearly how these stories have been used:

“We must get entirely clear of all the notions drawn from the wild traditions of original sin, the eating of the apple, the theft of Prometheus, the opening of Pandora’s box, and the other fables, too tedious to enumerate, on which priests have erected their tremendous structures of imposition, to persuade us, that we are naturally inclined to evil.”

— Mary Wollstonecraft (1792), A Vindication of the Rights of Women: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (quoted from http://www.eoht.info/page/Pandora’s+box)

More recently, it has become generally accepted that the Israelite story dates to something nearer to 500 bce, around some two hundred years after that of Hesiod. Palestine at that time was something of a crossroads between Europe, Asia and Africa – far more ‘cosmopolitan’ than ‘sunday school history’ would suggest. It is therefore entirely plausible that the Pandora story is directly the precursor for that of Eve – both are still used remorselessly to this very day as misogynistic propaganda.

Nearly all websites and books will just repeat the same nonsense of Pandora as ‘the first woman’ – apparently, prior to that point, humankind really was just ‘man’. For me, a reference source’s approach to Pandora is a good test of its reliability. Philosophers who accept the Hesiodic story can at best only waffle about the ‘riddle of femininity’ and the meaning of Hope remaining in the Jar. The majority seem to think Hope is delusory, rather than a comfort. A few might suggest that the difficulties of mortal life can be a worthwhile challenge to spiritual growth.

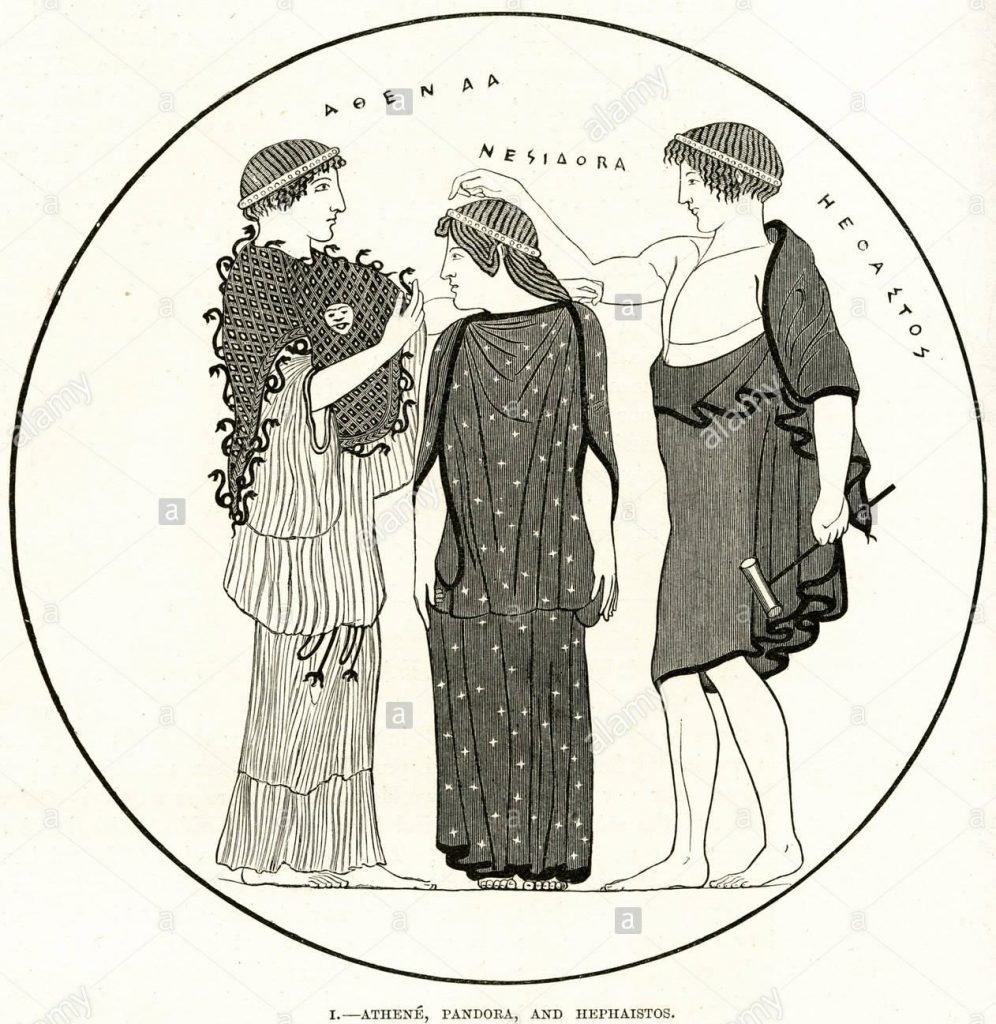

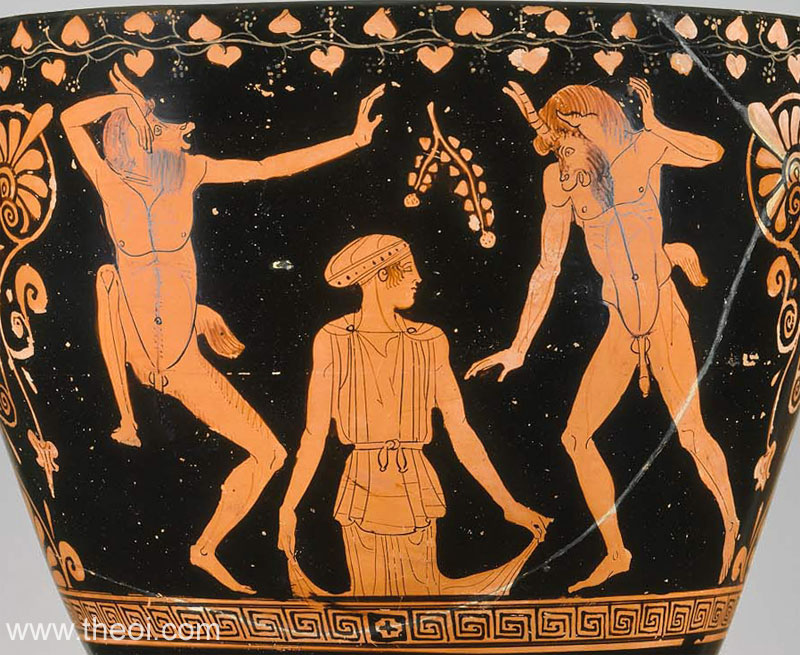

So how do we recover Pandora? What might her imagery and story be ‘really’? As it turns out, we don’t have words, but we do have pictorial evidence. The birth of Pandora was represented on the pedestal of the statue of Athena situated at the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens – hardly the location for a sadly moralistic fable. Long after Hesiod, vase painters continued to illustrate Her more properly.

The first modern scholar to break open the box seems to have been Jane Ellen Harrison, a Classics scholar at Newnham College, Cambridge in the early years of the 20th century ce. She was a feminist and a pacifist, a fighter for women’s educational rights (herself denied degree and professorship), much abused by male scholars unable to challenge her scholarship. It would be nice to think of her as a proto-Pagan, but though her work is of great value to us, she remained an atheist-humanist, and did not truly celebrate the Goddesses she liberated. She generally sees the myths as ‘explanations’ of ancient rites, the real nature of which – differing from Olympian religion – had been forgotten.

Harrison’s article “Pandora’s Jar”, published in 1900, first lifts the ‘great lid’. She links the Pandora story to the festival of Anthesteria (timed around the January or February full moon. The three days of the feast were called Pithoigia, Choës, and Chytro – all words related to ‘pots’. She shows how the festival, rather than being an excuse to open new wine, was rather, or was formerly, a celebration of the spirits of the dead – sometimes known as Keres.

.

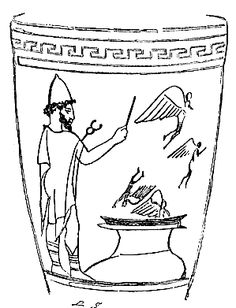

This vase shows Hermes, in his role as psychopomp, alongside spirits emerging from the pithos, one of which is returning to it. (redrawn by Jane Harrison after original in a dissertation by Paul Schadow, 1897)

Pandora’s jar is specifically called a ‘pithos’ – this is basically the sort of ‘Grecian Urn’ one finds in garden centres nowadays for people to make into water features. A pithos is actually a very large jar, too heavy for anyone to just carry, typically situated on the ground, or partly within. A smaller jar would have been referred to as an ‘amphora’ or perhaps ‘urnula’. To use a pithos as water feature in this way is not inappropriate. The flowing, and ever-cycling waters are a good invocation of Pandora, for She is the One from Whom All Gifts Flow, and to whom all returns.

Harrison writes more of Pandora in her book “Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion”. She castigates Hesiod as ‘pessimistic’ and ‘bourgeois’ and as having ‘ugly malice’. The name ‘Pandora’ means “the All-Giving”. It’s neither an ‘Olympian jest’ nor a sarcastic euphemism. Hesiod tries to switch the meaning into passive mode, as ‘all-gifted’. Wordplay of this nature is typical of mythic inversion. Harrison argues convincingly, from the evidence inscribed on the ancient pottery, how ‘Pandora’ is a title of the Earth Mother, in Her ‘Anodos’ – as Koré, the Maiden Uprising. Another name inscribed by Her image is ‘Anesidora’ – ‘sender-forth of gifts’.

As well as for storing the physical gifts of the Earth, the pithos was also used for funerary purposes – a practice not so dissimilar to the ‘Canopic Jars’ of Egyptian rite. Pithoi were often partly sunk into the ground. So the pithos is also the grave. The belly of the Jar is the Womb of Pandora. Images on surviving Greek pottery show pithoi as containing the ‘Keres’ – not ‘demons’ but the souls of the dead that are in Pandora’s care. The Keres are depicted as little winged beings – She sets them free.

The hubris exhibited by Hesiod is quite breathtaking. He has transformed the Mother of the Gods into their created plaything, a foolish, disobedient girl. He has turned Her Gifts into things of fear and contempt. He has turned our Mother into a vengeful curse upon humankind – “a woe for men who live on bread.” And clearly Hesiod doesn’t approve of curiosity – of asking questions. All of this is a perfect example of what Robert Graves calls ‘iconotropy’ –the re-interpretation and perversion of ancient religious images in the service of a contrary dogma. Poor Eve has much the same problem with Her Tree, Her Snake and Her Apple of course! We might feel a little sorry for this pathetic woman-hater and his unhappy private life, were it not for the torrent of bile for which he is responsible.

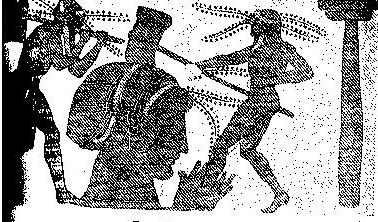

A tantalising hint from an ancient writer remains. We are told that Sophocles wrote a play entitled ‘Pandora or the Hammerers’. Sadly, the text has been completely lost; all we have is this title. Sophocles’ creation was apparently a ‘satyr play’ – we might think of this as equivalent to a farce, so some incongruity is plausible. The few writers who mention the play seem to think that the hammers might be used in breaking the earth, to free Pandora. Clearly they have never actually used a sledgehammer (which is what is depicted on the pottery). Hitting the ground with one of these things either splatters oneself with mud, or serves to compact the soil (not good for fertility). They could be used to break rocks, but that doesn’t make sense either, except for the use of marl to ‘sweeten’ acidic soil. ‘Clods’ are just too soft for hammers, and would need more than bashing to get into fertile receptivity. No one has considered what seems to me to be an obvious answer – the Hammers are used to smash the pithos in a ritual enactment, either setting free the spirits therein, or in the metal-working context discussed next.

The Hammerers are Pandora’s immediate connection to Hephaestus – he is always depicted with hammer in hand. His involvement opens a different or complementary thread of inquiry. According to Hesiod, Hephaestus is Pandora’s creator – other stories tell of his creation of metal-working automatons (we might call them ‘robots’ ). He is also assigned ‘patron god’ status for pottery. Hephaestus is generally considered ‘pre-Greek’ (that is, worshiped by people in the area prior to the arrival of Indo-European Greeks), as also was his parthenogenetic mother, Hera, Queen of Heaven. If we apply a process of ‘mythic re-inversion’ – a questionable methodology maybe, but which at least gives us a different perspective – we could have Pandora ‘correctly’ as Hephaestus’ mother.

This makes more mythic sense than you might initially think. Pandora herself is usually considered mother of the first mortal woman, Pyrrha. Together with her husband Deucalion, Pyrrha survives a Greek flood. It has been suggested though that Pyrrha and Deucalion are something of a fire / water allegory rather than ‘real characters’. ‘Pyrrha’ means ‘fire’, as in our various ‘pyro-‘ words. But in some non-Hesiodic stories, Pyrrha is credited instead as Pandora’s mother. Pandora is also closely associated with Fire via the Prometheus story – basically as the ‘pay-back’ and equivalent for Prometheus’ stealing fire from the Olympians Gods. We might easily say that Fire was the First Gift – that which facilitated our own species’ transformation from ‘animal’ to ‘human’. It is surely the case that Fire is the Mother of Pottery. Further though, metal-working was developed thousands of years after pottery, and could not have done so without the high-temperature technology of the kiln. Molten metal requires a container – specifically a robust pot. In some techniques, the container needs to be smashed in order to obtain the metal. We call such metal-holding pots ‘crucibles’ and we continue to use this word as a metaphor for the context of spiritual change. Breaking the mould is usually unavoidable when the intended result is a casting, such as a statue. So, additionally, the Pot is the mother of the Bronze.

Pandora’s Fire is a mix of Ancient Greek choral storytelling with a modern twist, perhaps intended mainly for school audiences. See https://www.theatrefolk.com/products/pandora-s-fire It’s somewhat off mythologically, since starts from the Box, but shifts so to completely subvert the victim-blamming of Hesiod. I love the ending:

Burn, burn, Pandora’s bright fire,

Dazzle the world with your light.

The modern writer Daniel Ogden makes the fascinating suggestion that ancient Greeks understood the Jar (maybe smaller than the usual pithos) as a container for Pandora’s child – a ‘teras-baby’, that is, ‘deformed’, lame or just ugly. Strangely he does not name this child as Hephaestus, despite the precise match that God would make to these labels. If all this mixture of imagery is confusing, well, that is precisely the nature of most true myth – they are an attempt to set down a coalescence of spiritual visions.

Fascinatingly, the ancient Greek word for ‘pot’ relates not only to ceramics, but also to chasms and fissures in the Earth, just as in the English ‘pothole’. Springs, the waters of life, flow from such pots. Even the phrase “gone to pot”, meaning ruin and destruction, translates similarly. We know that Persephone the Koré descends through such a place and returns thereby in Her ascent, Her Anodos. So the Jar is not just the holder of Pandora’s Gifts – it is also Her embodiment and Her gateway into epiphany.

I had always thought of Pandora as primarily an ‘Earth Goddess’, Waters too, but on reflection She would seem at least tri-faceted – like Persephone she is involved in Death / Rebirth but also, uniquely in Greece I think, but maybe not unlike Irish Brighid, in Fire, pottery and metalwork. If we take the view that Goddesses do not always have quite the same uniqueness of identity that we believe of ourselves, then Pandora would be a title not only of Gaea / Rhea or Persephone, but also of Hera.

I first made my own dedication to Pandora many years ago. Back in the Typewriter Age I published a magazine, itself titled “Pandora’s Jar”. At the same point in time, I rededicated my Fellowship of Isis hearth or Iseum as the Centre of Pandora, and I made dedication to Pandora at my ordination in the FOI. In addition to the factual material presented by harrison, I was very much moved by Charlene Spretnak’s retelling of the Pandora myth. I wrote back then that the reclaiming of the truth of Pandora is a good metaphor for the task we face. It is even more urgent now. Instead of dominating, fearing and cursing the Earth (and women) our society needs once again to live in harmony with the gifts She so freely provides. We also need to understand that the creatures that we find inconvenient or which sometimes bring us sickness are Hers too, older than We. The great gift of life is matched by the gift of surcease, of death, that we may live again, renewed in vigour.

Recent reading makes me feel further that the Giving of Gifts is actually the basis of human culture, not some add-on twice a year. Pandora as All-Gifting becomes then more than metaphor, rather the origin of whence we have come, and the focus to which we need to return.

Pandora, Anesidora, Koré,

Crowned With Flowers, First of the Graces,

You that bestow all things necessary to life.

From your never-emptying Jar

Come all the Gifts of Earth in season.

When we are constrained in rigidity

May your Hammerers Strike,

Set us free to grow.

May Your Hope Uprise Within Us like Your First Gift of Fire.

Rise Up O Flame

May we be transformed in Your Crucible

As Gifts of Beauty, Wisdom and Joy.

References:

If you’re as fascinated by Pandora as I am, you might be interested in these sources – if you find others, of interest beyond the same old stuff, please let me know:

- All the original texts are online, for example at www.theoi.com/Heroine/Pandora

- Wikipedia will give you a good basic introduction: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandora

- Jane Harrison’s work is not easy reading … she expects you to be able to read Greek and Latin without translation, and the word ‘phallus’ stays in Greek! The original “Pandora’s Box” article seems only available via the Journal of Hellenic Studies, just this purchasable at: https://kisslibrary.com/book/BB07C132C1F96EB0B4A6. Her “Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion” can be bought easily from Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Prolegomena-Study-Religion-Classic-Reprint/dp/0266343619/

- Daniel Ogden. “What was in Pandora’s Box?” is in “Archaic Greece: New Approaches and New Evidence” edited by Nick Fisher, Hans van Wees. I read it at https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=fARPDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA213&lpg=PA213#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Charlene Spretnak. “Lost Goddesses of Early Greece” is a wonderful collection revisioning the myths – https://www.amazon.co.uk/Lost-Goddesses-Early-Greece-Pre-Hellenic/dp/B017QUZEVG/

- Dora and Erwin Panofsky produced a fascinating study of the changing imagery of Pandora – free pdf from: https://monoskop.org/images/4/40/Panofsky_Dora_and_Erwin_Pandoras_Box_The_Changing_Aspects_of_a_Mythical_Symbol.pdf

- An interesting account of Jane Harrison and her critics is ‘For love of an idea’ by Arlen Shelley: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09612029600200114