An exploration of the Probabilistic Fallacy and alternatives to it

As Pagans, particularly as NeoPagans, we are overwhelmingly interested in the Past. We don’t (necessarily) have a romantic or otherwise rosy-tinted view of former times. We simply want to know more about both the material lives and the spirituality of our ancestors. We generally believe that for them a closeness to, an understanding of and a unity with the Deities and Spirits generally was something normal and known from immemorial times. We who live in a culture utterly alienated both from spiritual meaning and from one another often despair of the struggle that we have in making meaningful contact with the Spiritual Kindreds.

Unfortunately, our knowledge of the past is desperately inadequate – less clear than a blizzard at moonless midnight. But we do our best to interpret, infer and extrapolate from the pitiful remnants of pots and bones and, where our ancestors were actually literate, from the generally incoherent textual fragments.

The point of this essay is to challenge (indeed completely to refute) the use of certain ‘probabilistic’ words in discourse regarding the past. These include ‘probable’, ‘possible’, ‘probably’, ‘possibly’, ‘likely’, ‘perhaps’, ‘may have been’ and so on. You can find them in almost any work opened at random. These usages are to be found in all registers, from the most ‘popular’ to the impenetrably academic.

You will certainly have seen many similar such statements. My personal favourite is the use of ‘almost certainly’, which for a number of authors characteristically seems to precede a wild flight of fancy. As an easy test, try Google for ‘druids probably’ and see what sort of stuff you get – here are some:

1. a quote from the British Museum site,

“Archaeologists rarely find direct evidence for priests in the Iron Age. But they often find evidence for religious rites and sacrifices and many of these were probably carried out by Druids.”

2. in an OBOD page:

“we can see that the Druids probably acted not as mediators of Divinity, but as directors of ritual, guiding and containing the rites. “

3. somewhat questionable in its substance perhaps, I spotted a work by one Geoffrey Higgins (1829) titled “The Druids Probably Pythagoreans” (didn’t bother to read it!).

4. On the ADF site for ‘probably’ this from the late and now excoriated founder Isaac Bonewits (https://www.adf.org/rituals/explanations/stepbystep.html)

As near as I can figure, Quarter invocations probably weren’t necessary for Paleopagan Druid ceremonies, since (a) everybody probably already knew which direction was which, so the orientation factor was covered

Or for a taste of somewhat less rigorous thought processes, try looking for “Jesus probably never existed”.

The problem with this sort of writing, the fallacy that it contains, is quite simple. Druids (whatever they were, since that issue itself is less clear than mud) either did, or did not carry out ‘religious rites and sacrifices’. Druids either did or did not act as ‘directors for ritual’ or as ‘divine mediators’ (though these concepts are in no way mutually exclusive). They did or did not know which direction was which (we might presume the former, despite the uncertainty of many modern Pagans). They did or did not celebrate equinoxes and/or solstices. And as for my last example ‘Jesus’, as a purported human being born of a mother, quite definitely either did or did not exist. No specific human being can ‘probably exist’.

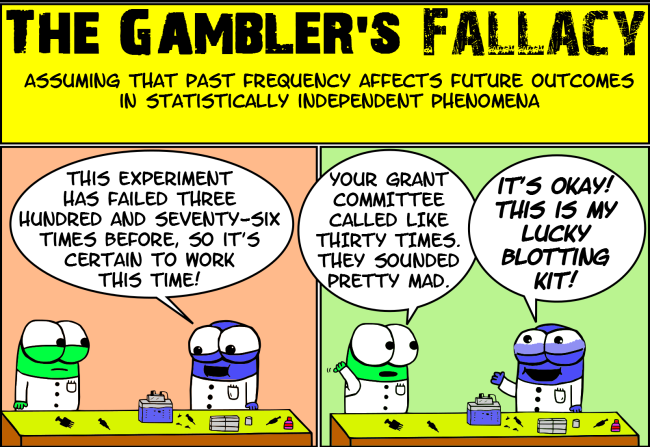

In these cases, and inevitably with similar phrases, there is actually no question of probability. The past happened as it did – the problem is our lack of knowledge. The use of probabilistic language is fallacious – which is to say, not so much ‘wrong’ as something that gets in the way of knowledge and understanding.

At this point my reader may be starting to protest. One argument is that the meaning or rather the usage of words changes over time (not by themselves, but by human choice) In the case of the word ‘probable’, a change did occur from around the 16th century onward. Prior to this point, ‘probable’ meant what we would now express as ‘provable’ (Cambridge History of word meanings), linked closely to ‘probity’ (good authority). The modern meaning, with implications of likelihood and chance derives from the mathematical / scientific study of gaming and chance. Look a little closer here and you can see that the modern meaning can even be said to have reversed the older one – for nowadays, if something is ‘only probable’ then there is also a ‘possibility’ of non-occurrence – so it surely can’t be ‘provable’.

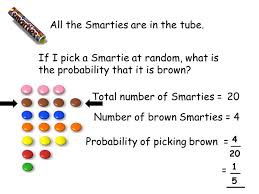

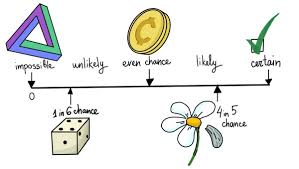

Wikipedia gives a simple definition. “Probability is the measure of the likeliness that an event will occur.” Note the tense. Probability refers only to future or hypothesized events – not to past (or present) ones. Probability theory, and developments from it, such as statistics, are based on the outcomes of large numbers of individually ‘independent’ ‘random’ events – such as tossing coins or rolling dice repeatedly. Probability is expressed as a number between zero and one (zero means ‘absolutely impossible’, one means ‘absolutely certain’) or as a percentage. When I was young, this subject was considered to be ‘advanced level’ mathematics. Nowadays, the basics are taught to children from primary school (though not with much success if one considers lottery sales!)

In ordinary (conversational) usage, ‘probable’ means ‘fairly likely to occur’ – so if forced to quantify this we might alternatively write of the issue under consideration that it has a probability of more than 75% (say). Conversationally, we might also use the word ‘possible’ for a probability less than 25% (say). Such usage is wildly inconsistent though. For example, on a main road near where I live, there is an official sign saying ‘Queues Likely Ahead’. So what really is the probability of encountering a queue taking longer than one cycle of traffic lights? Certainly queues do occur, especially on Friday afternoons and holidays. But if you computed the proportion of time with queues to that without, I suspect it’s only about 2% at most. A computation counting journeys experiencing a queue would give a higher result (since not many people drive at midnight) but still a very low value, much less than 50%. In this case, it is conceivable that the sign have saved a careless driver’s life, or one day will do so, hence can be forgiven.

In more scientific usages, the numbers in use are quite different. If you were trying to sue a company on the grounds that its practices or products had made you ill, the court would require at least ‘99% certainty’ before awarding in your favour. Drug trials and all other such testing likewise require this level of ‘proof’. Mathematically the meaning is subtly different, these numbers are not a percentage of ‘proof’ or ‘certainty’ but rather a double negative – the probability that the opposite effect occurred by ‘chance’. For example, if one throws a coin 20 times and gets 17 heads, one might ask “Could the coin be biased?” The answer to this question is always “Yes, certainly could be” but this answer is worthless without quantification. In fact, the maths computes that, if the coin is unbiased (this is called the null hypothesis) the probability of 17 or more heads out of 20 is (via ‘binomial calculator’ from Google) approximately 0.0013, also expressible as just over 1 chance in 800. You might well be suspicious, and inclined to ‘reject the null hypothesis’, but if bored enough to do many such sequences of throws with a genuinely unbiased coin, 17/20 would indeed be expected to happen at around the one-in-800 frequency. (The more precise wording of this ‘law of averages’ is called the ‘Central Limit Theorem’).

So consider how this applies to the use of probabilistic language for events of the past. No one ever specifies, even as a wild guess, any numerical value for a ‘past probability’. Of course, they cannot do so. Not only did past events simply happen as they did, they were unique, not repeatable, as is the first requirement for probability theory. Although we might argue, for example, that each future horse race or sports game is unique, we have seen so many of such similarity that reasonable probabilistic prediction is possible (at least enough for gambling businesses to prosper). But the past events under discussion just aren’t like that.

My concern here is not at all to grumble about the rather poor understanding of probability theory shown by people in general, including academic writers with PhD degrees. It certainly is the case the probabilistic language is widely used to indicate a lack of knowledge rather than anything resembling mathematical probability. My assertion though is that the ubiquitous usage of ‘probably’, ‘may be’ and related terms is not a legitimate evolution of language but rather is (a) fallacious in itself and (b) actually constitutes a deliberate obscuring of knowledge.

Perhaps you feel that I am ‘overstating’ my case. So here’s a couple more examples, from the thoroughly academic ‘Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt’.

1. From the article about ‘Childhood’, concerning education of girls: “Daughters of noble families probably also had home instructors…

This statement refers to a ‘population’ and so resembles ‘shorthand’ for something on the lines of “if a noble family were chosen at random there was a 75% probability of a daughter having a home instructor”. But to make such a statement would of course require reliable quantified data, which does not exist at all. However, I have no doubt that if the writer had such a precious nugget of information then she would have quoted it directly. So the probabilism is there to hide what is really an ‘educated guess’, and hence is fallacious, even though I suspect its import is accurate enough.

2. From the article about ‘Chronology’, concerning the Hyksos invasion: “It is probable that the remnants of the ruling house of the thirteenth dynasty fled to Thebes…”.

This refers to a specific historical event, so that the probabilism is there to hide the lack of precise documentation. (Even though it’s difficult to see how any other guess at events would be remotely plausible.)

What we are really doing when examining the past is not looking for ‘proof’ but rather simply for ‘evidence’. We are used to the idea of evidence being ‘weighed’ (in legal process) in order to make a binary decision – guilty, yes or no. We may describe certain types of evidence as being ‘weightier’ than others. This isn’t a very good metaphor. A better one is now well-known – most people are familiar with digital imagery such that when expanded beyond its proper level of resolution, the picture appears ‘fuzzy’. This is very much the character of the past. More evidence sharpens the images, but still we are at best peering at mostly incomprehensible fuzziness. You may well be aware that fancy computational maths can be used to ‘sharpen’ images such as those of car number-plates – but this is only possible because we have a firm ‘model’ for such images – that they consist solely of dark characters (a choice of 36 well defined shapes) on a pale background. The matching of facial photographs to existing images is dramatically more complex (as well as being highly questionable in political intent), currently still far from being a ‘certain’ process. But it still relies on the fact that we all have two eyes, a nose, mouth, ears etc. Whilst we presume Druids were similarly equipped, we know so little further about them that their identity, ideas and activities continue to be hopelessly ‘fuzzy’.

My assertion about the use of manifestly fallacious probabilistic language is that it is not ‘just a mistake’, but rather that it is deliberate, for a purpose I consider illegitimate. As one makes one’s way through the ‘educational process’, one of the themes that gradually develops is the distinction between ‘fact’ and ‘opinion’, or alternatively, between the ‘objective’ and the ‘subjective’. This used not to be considered much before university, but nowadays, saturated as is our culture with ‘fake news’, propaganda, advertising and PR in general, the idea of distinguishing fact / opinion is taught at a much earlier point. One of the motifs in such discussion is whether or not any claim is ‘scientific’, since ‘science’ is often presented as guaranteeing ‘fact’. The history of science and the claims of scientificity is somewhat less than reassuring. The dramatic development of the study of ‘physics’ in the 19th century greatly encouraged a claim of scientificity for almost anything. Marx and Engels claimed their concept of socialism was ‘scientific’. Madame Blavatsky made similar claim for her vast outpouring of twaddle. Distinguished classicists ‘proved scientifically’ that ‘Mycenae’ and ‘Troy’ were ‘just myths’ (until Schliemann came along with his shovel). Even in physics things are far from clear – if you study the subject at university you will soon discover that everything you were taught as ‘facts’ and ‘laws’ is actually no more than ways to make fairly good guesses of everyday-world events, but useless at the scale of electrons or planets. .

A number of writers have demonstrated the inadequacy of the binary terminology such as ‘objective / subjective’, ‘fact / opinion’, ‘scientific / unscientific’ etc. But this opposition very much remains a standard criterion for judgement. Supposedly, the ‘most objective’ of all disciplines is mathematics – the more mathematically an idea is presented, the more ‘scientific’ and ‘objective’ it is considered to be. If the language of mathematics can be appropriated in any other discourse, that discourse is considered to achieve ‘objectivity’ and ‘scientific’ character. Probability is certainly a mathematical concept, but the generalized use of its language is directly intended to confer ‘objectivity’ when actually the matter of interest is irredeemably ‘fuzzy’.

A recent example of precisely this. See https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ archeologists-found-almost-2000-gold-spiral-objects-bronze-age-180955943/. This is from the magazine of the Smithsonian Institute, from which one might hope for genuine ‘objectivity’. The headline is

“Archeologists Have Found 2,000 Ancient Golden Spirals and They Have No Idea What They Are”

An honest headline, but the first sentence then says “The meaning or purpose behind the spirals is unclear, but they probably were part of a ritual”

We all know of course that the use of the word ‘ritual’ by archaeologists is their ‘code’ (that is, a pretension of knowledge) for “haven’t got a clue” (See https://www.thepoke.co.uk/2018/12/31/18-euphemisms-for-i-havent-a-fcking-clue-that-make-ignorance-seem-really-intelligent/ for more!) But consider how the ‘probably’ is used above so as immediately to convert ‘no idea’ into a purportedly ‘objective’ statement.

So, in this case, and more generally I assert, the use of the fallacious probabilistic terms is intellectually fraudulent. Its purpose in all cases is to attempt to hide the writer’s lack of knowledge and present that absence as if genuine ‘objective’ knowledge. If you poke around any interesting tome, you will find examples on almost every page. If you’re a bit bored, you could even compute p3 coefficients (probabilisms-per-page). It wouldn’t be so bad if the writers generally presented evidence for and against a claim of probability, but all to often the words are used as a substitute for evidence, ‘ex cathedra’ one might say, so that one is obliged to but trust (or otherwise) the ‘authority’ of the writer. ‘Appeal to Authority’ is indeed well-attested as a standard form of fallacy.

Sadly, this way of writing is heavily encouraged academically. It is comparatively rare that you will find anyone writing “I think that…” or more honestly “My guess is that …”. Academic writers not infrequently seem to want to stress their own ‘authority’ more than honestly to present information. Any explicit ‘subjectivity’ is derided. I recently found an example in Richard Wilkinson’s ”The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt”. This is a very attractive book, well-regarded by academic and wider audiences. Intriguingly, of Sekhmet he writes “Statues of Sekhmet can still inspire feelings of awe”. As stated, this is certainly true, as many of us may attest. Yet Sekhmet is the only deity of whom he mentions such a response. I rather suspect the author would have liked to say that he himself feels such awe before Her. But dared not, lest his entire work and career be ridiculed for a single sentence.

So one can have sympathy for those writers in the Pagan community who produce well-researched and thoughtful work, yet who are generally not considered sufficiently ‘scholarly’ for the academic community. Some of these folk I know and would hope to count them as friends. The pressure on them is very much to use probabilistic language in convergence with academic writing.

Particularly annoying, I find, is the ‘compound probabilistic fudge’. This is shown in a statement on the lines of “evidence suggests that ancient Egyptians might have visited Britain”. From my argument above, the ‘might have’ is worthless. A non-fallacious statement would have been “evidence suggests that ancient Egyptians did visit Britain” (preferably with evidence, such as the presence of British-origin tin in Egyptian bronze). The word ‘suggest’ is quite sufficient to imply the fuzziness of evidence and that a claim of absolute and unchallengeable fact is not being made. Yet you will often encounter triple fudges – multiple probabilisms in a single phrase.

Does any of this really matter? Is it just intellectual trivia? Sadly, I think it does matter. It seems to me that the pretense of ‘objectivity’, the imposition of probabilism and the pretense that almost everything written about the past is not primarily interpretation and opinion, is also a denial of personal agency and responsibility in general.

As a more informal example, I might make a statement like “I shall probably go to the pub tonight”. Yet there is really no probabilistic content in this. The statement is not founded on an analysis of my past behaviour and the consequent hypothesized probability of my going to the pub on any randomly selected night. Rather, it would in some instances be a statement of intention that is still fuzzy (unfinalized) or else a pretense at fuzziness when in fact I had firmly decided to go to the pub, the phrasing intended as a ‘negotiation’ with a partner deserted to ‘Eastenders’. The latter variation, a denial of intention and agency, is a commonplace in day-to-day human interactions. I make no claim to be innocent of it. Nonetheless, it is a dishonest mode of communication.

Such personal trivia might not matter, some would say. But when we look at the state of the world, it seems to me that a major feature of most public discussion (politics!) is precisely this denial of responsibility and agency in almost every sphere of concern. A rapist might say the victim was ‘asking for it’; a murderer that ‘they had no choice’; capitalists say they are ‘providing work’ rather than exploiting surplus value; police gassing demonstrators are called ‘security forces’; wars are ‘humanitarian intervention’; and all that is before we hit the denial of Global Heating and Climate Emergency. So it’s not just the personal that is political, the probable is political too!

There is no need for the use of probabilisms. The English language has a plethora of possible forms. The simplest single-word replacement for ‘probable’ is the word ‘plausible’. Indeed, a general confusion seems to exist between the meanings of these words. ‘Plausible’ means that something can be ‘believed’, but with defensible reasons. More generally, an opinion may be presented as a guess, conjecture, hypothesis, postulate, speculation etc. Interpretations may be presumed, assumed, asserted, argued, ‘seem to be’ and so on. Any such term may be qualified with wild, tentatively, firmly and others as required. An author may resort to passive mode in general (‘it is thought that…’) or using semi-personal forms (‘one feels…’ or ‘we suggest…’). Collective support may be implied (‘it is generally considered…’ or ‘Most scholars take the view…’). Each of these innumerable variations has its own nuances of meaning, which are not necessarily the same for both writer and reader. (Yet, I suggest, less randomly interpretable than are probabilisims.) Nonetheless, all of them involve and require the active subjectivity of the author in expressing their view, and all actively invite the presentation of the evidence from which the judgement has been made.

So I would like to challenge you. If you are a reader, any time that you encounter a probabilism, consider how it might be rewritten appropriately. If you are a writer, have a look at your work and think about what you really mean… I was horrified a little while ago to find such a beast in my own published piece about Pandora in ‘Naming the Goddess’. We slide into these usages without thinking properly, so ubiquitous and ingrained is the probabilistic fallacy in all forms of language. (I have attempted to fix the blogged version of Pandora!)

Here’s an example, taken from “Egypt’s Annointing Mysteries” by Alison Roberts (a most interesting work well-provided with proper scholarly references and actually with quite a low p3). Of the New Year Rite, she writes (page 66):

“although it is impossible to locate the ceremonies specifically within any known Egyptian temple, in all likelihood they would have been performed in one of the huge sacred precincts in the north at Memphis or Heliopolis which has long since disappeared.”

In this, the phrase ‘in all likelihood’ is an unfounded probabilism. For the passage to be non-fallacious, a simple replacement for the otherwise not-at-all-contentious phrase is, I suggest, “we may assume that“. Where’s the problem with this? Would the sky have fallen to have used it instead?