In my news feed around last year’s Winter Solstice there was a item about Icelandic Pagans celebrating at their new temple site.The report is here: https://icelandmonitor.mbl.is/news/culture_and_living/2017/12/23/icelandic_pagans_celebrate_winter_solstice_at_new_t/ For the most part, it’s a reasonable presentation, but at the end the reporter just had to put in “As to the sacrifice, there’s no blood spilled at the ceremony.” The Gothi, Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson responded “No, no, this is very child friendly. The only thing we sacrificed were clementines.” Sounds to me like he was a bit grumpy over the s-word. Quite justifiably I feel – reporters in general seem quite obsessed with their notion of ‘sacrifice’, projected onto us.

But why are they so obsessed? I am inclined to feel that it is indeed their own (that is Christian) nastiness that they desire to project onto others. The Abrahamic religions in general have something of a cheek in doing this, for their religions are absolutely founded on the principle of ‘sacrifice’, that is, of killing in the name of their big-G. Not many people actually bother to read the Bible nowadays, other than a few cherries suitable for Sunday-school children, but its awfulness is there in black and white.

It takes just four pages to get to the first atrocity (Genesis 4:1-18) – Jehovah rejects Cain’s offering of ‘the fruit of the soil’ but accepts Abel’s choice lambs. Fratricide ensues. Sundry places in the ‘Old Testament’ document Jehovah’s delight in the “soothing aroma” of burnt offerings. Apples and lettuces clearly aren’t good enough for him. It is generally considered that the Cain / Abel story is ‘historical symbolism’, to do with conflict between pastoralists and agriculturalists. There’s no doubt some violence did occur in that historical context, as indeed similar economic difference has repeatedly through history. However, the evidence from multiple historical scenarios generally has the pastoralists causing the violence, so the story can plausibly be read as a deliberate case of ‘blame the victim’!

We refer to the Abrahamic religions as such since they claim Abram / Abraham (my ‘New English Bible’ seems to mix the names) as founder. By ‘submitting’ to J, or ‘Allah’, Abram is also considered ‘the first Muslim’. Pagans might well interpret this story somewhat differently – for me anyway, it demonstrates Abram’s absolute moral failure. Genesis 22 does not mention Abram having the slightest compunction at cutting his son’s throat (despite Isaac’s somewhat miraculous conception to a woman of 90 and a man of 100 – one might imagine the child as more valued!) Wondering what sense could be made of the story, I came across this article: http://www.chaimbentorah.com/2013/09/word-study-ram-thicket/, which describes the famous ‘Ram in a Thicket’ as illustrated. Apologetic though the article is, it suggests firstly that the Hebrew word ‘aval’ can mean any animal with horns, and then further that the image is of ‘Marduk’, also known as ‘Amar-utu’; that is, the calf of Utu (the sun god), hence ‘the young bull of the sun’. So that article argues that the ‘sacrifice’ story is really a symbolic statement of the death of the Pagan deity, with J taking things over.

If J was prepared to ‘save’ young Isaac, he was less bothered as to “Jepthah’s Daughter” – being female, she doesn’t even get a name. Her father ‘sacrifices’ her in thanks to Jehovah granting victory over the Ammonites. You can find her tale in ‘Judges’, ch. 11. Abrahamic apologists often try to deny this disgusting story. As for animal sacrifice, it is precisely specified that two yearling lambs should be killed every day at the Hebrew Temple. (We don’t really know whether this rule was really complied with, since it’s a vast quantity of creatures for a supposedly poor folk, or whether the whole idea is all just the writer’s fantasy.) Yet apparently, a ‘sacrifice’ of a lamb is now being performed by the ‘Jewish Institute’ in celebration of the passover festival. (Source: https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-first-passover-sacrifice-to-take-place-in-old-city/) One could go on, ad nauseam – the Bible is full of such stuff.

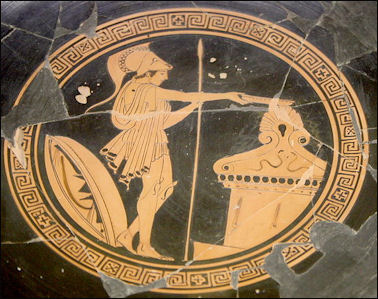

Archaeologists too seem to be obsessed by ideas of ‘sacrifice’. All forms of violent death, human or animal, are guaranteed press coverage and exhibits of the remains. There’s always been a big gap between ‘animal sacrifice’ and ‘human sacrifice’ – the former was clearly a widespread practice in classical (Greek / Roman) religions, yet the latter is only hinted at in myths, to the point that some question whether human sacrifice was ever actually practised. These historical Pagan cultures certainly did kill people of course, in the context of ‘execution of criminals’. What makes a ‘criminal’ is, as nowadays, not consistent – the famous philosopher Socrates famously found this out the hard way.

My own view is that ‘human sacrifice’ was always the deeply ‘political’ matter that it is to this day – a matter of power and control in which any form of spirituality is just conscience-appeasement and public relations. I would assert that there is no significant difference between ‘execution’ and ‘human sacrifice’ – we should certainly consider that the killing of ‘witches’ was the latter. So, contrary to the official view, I would argue that human sacrifice in Britain only came to an end in the 1960’s when execution by hanging was abolished. Calling the process ‘execution’ makes no difference – it was a highly ritualised killing, fully sanctioned by a representative of the state religion, the ‘Church of England’.

The media obsession with ‘sacrifice’ is particularly galling, for modern-day Pagans, in that ‘sacrifice’ is something we have (almost) completely renounced. The most famous of such renunciations is the one in Doreen Valiente’s “Charge of the Goddess” in which She states “Nor do I require aught in sacrifice, for behold, I am a gracious Goddess and my Love is poured out upon the Earth”. This is an excellent summary of Gift-Economy Theology.

Various public-facing Pagan organisations with which I am personally involved, such as the Fellowship of Isis, and Ar nDraiocht Fein (A Druid Fellowship), explicitly prohibit any form of ‘sacrifice’ in their rites. And yet, it is fascinating that at almost any Pagan event, someone will inevitably make a ‘sacrifice joke’. Few, if any, are amused, yet whereas sexist and racist ‘jokes’ would nowadays be called-out, this doesn’t much happen with ‘sacrifice jokes’. Most Pagan events are indeed considerably less orgiastic than a Sunday-School outing, and one can perhaps forgive those who wish they were rather more wicked.

Given the apparent significance of ‘animal sacrifice’, at least in the comparatively well-documented classical world it is not surprising that some Pagans have, Valiente et al notwithstanding, wondered whether some form of ‘sacrifice’ should be reinstated, for example, at major festivals where ‘hog-roast’ or suchlike would be taking place anyway. Although vegetarians might not care for this, it is argued that the creature should be killed humanely, thanked and honoured – which certainly does not happen with abbatoir meat.

It is difficult to understand any sort of rational explanation for animal ‘sacrifice’ except in the context of communal feast. Indeed, the whole business seems somewhat crazy. I read recently (in Sorita d’Este’s just-published “Circle for Hekate”) that the chronicler Hesychius of Miletus wrote that dogs were sacrificed to the Goddess Genetyllis (associated with Hekate) in order to reduce pain in childbirth, on the justification that dogs were thought to have less painful labour. He wrote in the 6th century ce, so might well be misinformed.

Hekate is certainly known both as a ‘lover of dogs’ and as a friend to women in childbirth. But the ‘logic’ escapes me. I would have thought Hekate displeased by people killing her creatures… More generally, I absolutely reject the notion of the Deities as capricious and hostile beings that require appeasement. I similarly reject the idea that they need the ‘energy’ or ‘mana’ from killing-sacrifice – rather, the God/dess/e/s are the source of all ‘life’ and ‘energy’. Those of Hellas lived on ‘ambrosia’. (And in Asgard, Odin consumed only wine.) So they really didn’t need burnt offerings and smoke.

One can wonder therefore how the notion of ‘animal sacrifice’ might have arisen, unless one dismisses it as ‘primitive superstition’, or otherwise takes it as purely a form of manipulation of the masses by a parasitic priesthood. Those views might be taken by rationalists and Abrahamics, but surely not by Pagans. Nonetheless, I cannot see how the ‘dog sacrifice’ described above can derive from a valid spiritual vision. In pursuing these thoughts, I was inspired to the following perspective. I haven’t worked through the vast academic literature on the subject – I would be most interested if anyone has additional reliable information in support of my thesis (or even if there is real counter-evidence!)

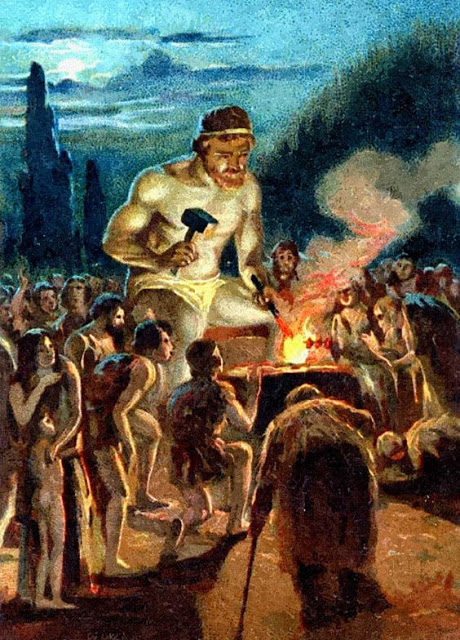

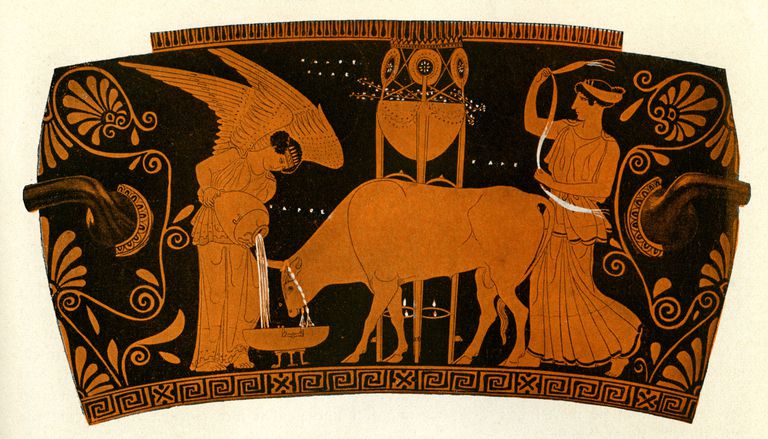

I was struck by the similarity of two individually well-known mythic stories. The first is Greek – the establishment of animal sacrifice by Prometheus (as related by Hesiod). The point of this story is that what Prometheus actually ‘sacrifices’ (that is, burns on the altar) is really a bundle of skin, bones and unappetizing bits, saving the meat for humankind (which Prometheus had just created). All the usual interpretations take Greek myth as ‘drama’ (by which I mean human interaction, rather than sacred story), and so this episode is regarded as a ‘clever trick’ at the expense of Zeus, who then has ‘justification’ for his subsequent sadistic cruelty to Prometheus.

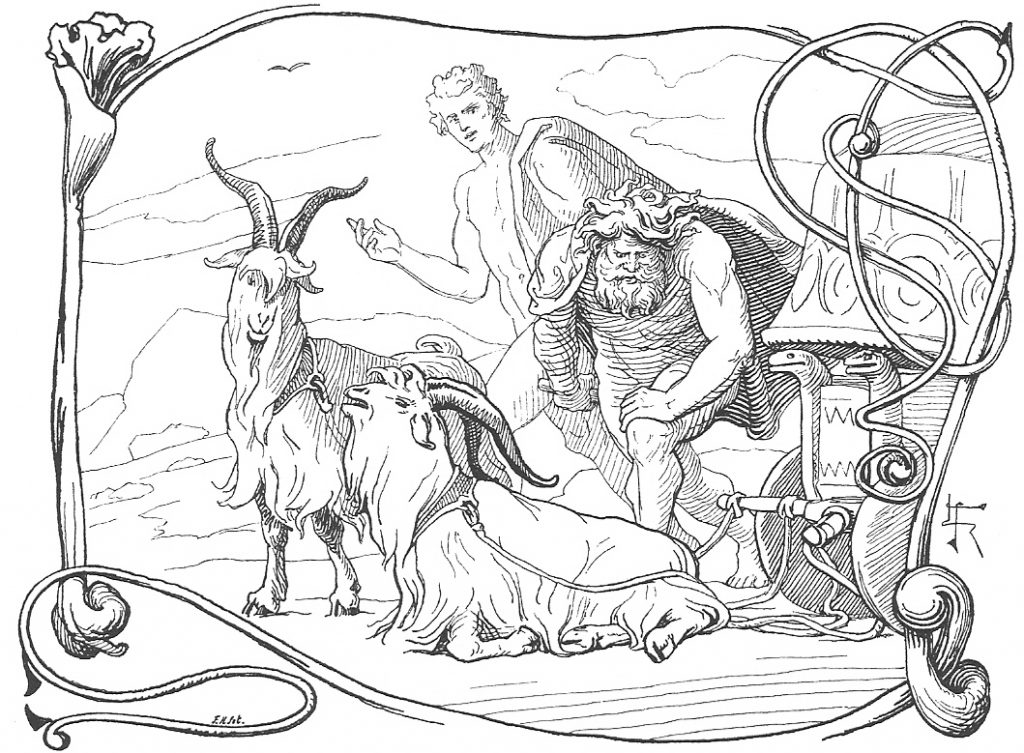

The second is Norse, from the story of Thor’s visit to Utgard. Thor kills his goats, as meat for dinner at a farmstead where he stays. He specifically requires bones and skin to be set aside, and next morning, he ‘hallows’ the two piles (using Mjolnir, his ‘hammer’) and they are returned to life as goats. The whole story is usually treated as near-slapstick, and as an incidental excuse for Roskva and Thialfi being taken into Thor’s service. Alternatively, the episode might be considered an example of ‘magic’ – which doesn’t really tell us much if we consider that Thor, like all deities,, is 100% magic anyway.

For us modern folk, cursed by the Book, we tend not to realise that ancient sacred story (aka ‘myth’) was transmitted as much by visual means as by oral retelling, and not at all by fixedly printed words. In addition to wall paintings and art on ceramics, myth-depicting tapestries were highly valued (women’s work of course…) and we have specific record of wood carving being used as myth-depiction in Scandinavia. I have not been able to identify good images, neither ancient nor modern, of either of the two specific scenes (lots of Prometheus being tortured, and of Thor in chariot with live goats) – but if we imagine the two scenes, I think we might well be unable to distinguish between them. We don’t know whether Prometheus blessed his ‘sacrifice’ by hand-waving or with any implement. However, it seems to me that in the closely-linked myth of Pandora (see also my post: Pandora Unboxed) Prometheus is in places mythically doubled by Hephaestus, who certainly is a Hammerer, so that a hammer is plausible in Prometheus’ grasp also.

My contention firstly then, is that these two stories are later reflexes of a much older, shared Indo-European spiritual tradition. I’m happy to accept the tenet (much used by Jane Harrison and the ‘Cambridge school’) that the praxis of a rite is deeply conservative and may be much older than the explanation or ‘myth’ associated with it. The story of Thor is not, of course, called a ‘sacrifice’, since he revives the goats rather than killing them. My contention is that actually, Prometheus was ‘originally’ considered to be doing the same thing. He clearly is not killing the creatures, since that happened some time prior.

Academics, for whom dinner is put on their plates by someone else, may not be aware of how time-consuming a process butchery actually is. The creature has to be beheaded, bled, eviscerated, skinned and jointed. Often, meat is ‘hung’ for at least a few days before cooking. We are told that at one festival of Panathenaia, for example, Athena received a sacrifice of 100 oxen, which were then used in a great banquet to feed the worshipers. No one ever tells us how many butchers and cooks were involved, nor how long it took them to get the meat from living animal to worshipers’ plates.

We must understand though that the myth of Prometheus is not ‘just another story’ but rather is the primary precedent, the mythic / theological justification for, and the exemplar of sacrifice in Greek religion. So if his rite is manifestly not one of killing, but rather one to effect rebirth of the dead creatures, that completely explodes all ‘rationale’ for ‘sacrifice’. Thor, being a deity, effects revivification immediately – we mortals, following Prometheus, have to trust the Gods to do things in their own time.

It seems to be universal in hunting cultures that, whilst valuing the skill of the hunter, it is always considered that the animal ‘gives itself’, generally with the mediation of a deity sometimes known as ‘Master of the Animals’ and otherwise as ‘Lady of the Beasts’. It is always the case that prayers are made at the killing: firstly for the arrow or spear to fly true, bringing a quick and clean death; secondly in thanks for the gift of life, to both creature and deity. But this is not ‘sacrifice’, just dinner. More theologically, it does not meet the criteria for the usual view of ‘sacrifice’, since it is not the hunter who ‘gives’ the animal to the deity, but rather the opposite – the deity gives the creature to us.

I do not have information as to whether the ‘skin and bones rebirth rite’ is something specifically Indo-European or more widespread. I strongly suspect that other cultures have different practices, but still focused on the rebirth of the creatures’ spirits. Anthropologists, viewing through the muddied Abrahamic lens, are all to likely to have referred to such ‘primitive’ rites as ‘sacrifices’. It would be interesting to know of other traditions in which alleged ‘sacrifices’ might more properly be revivifications. The only other such rite that I know of is the ancient Greek “Bouphonia” described in Harrison’s “Themis” – in this, after all have eaten of the flesh, the ox skin is stuffed with hay and stood up together with a plough as if alive.

Human beings have been killing animals and eating meat for as long as we have been standing on our back legs. It is now widely understood that ‘gathering’ generally produced more calories than ‘hunting’, but this tended to make meat-eating something ‘special’, as it still is for a great majority of the world, unless explicitly vegetarian. So why should killing a creature in a fancy way become something religious? I have argued that what we now call ‘sacrifice’ conflates two quite separate events of religious significance – the death of the animal and the later ‘rebirth’ rite. These events are separated by a substantial time interval. It seems to me that whilst ‘sacrifice’ is generally considered ‘nasty’, both the above are perfectly valid rites for meat-eaters. I appreciate of course that vegetarians may feel it is time for ‘spiritual evolution’ beyond all of this.

I think we have to assume that the notion of ‘sacrifice as killing’ derives from the time when humankind shifted from gathering-hunting as ‘mode of production’. It is tempting to ‘blame’ the Indo-Europeans herding culture for originating the notion, but early farmers can just as plausibly be the culprits, or indeed the fusion of these cultures may have triggered it. Both herders and farmers think that they ‘own’ animals and further that they themselves are responsible for the animals’ breeding. Freud and other psychologists have built vast theoretical edifices on the idea that killing animals for food produces ‘guilt’ within humans, and that this is the real basis of ‘original sin’ and all other religion. I find this argument wholly specious, and rather, that is the theological / conceptual shift from the twofold prayer-at-death / subsequent revivification to the notion of ‘sacrifice as killing’ that is the ‘Original Heresy’.

So where does this leave modern Pagans? Not many of us, even if meat-eaters, have the option of killing and butchering the meat we eat. Were we so forced, one suspects the number of vegetarians would rapidly increase! But it does mean that if context and circumstances allow – the festival hog-roast for example – then it’s not invalid to treat the animal’s death as a spiritually meaningful event and hence to give appropriate prayers and thanks at that act. Nor would it be invalid to perform the ‘skin and bones hallowing’ or other revivification rite. Nonetheless, neither of these should actually be referred to as ‘sacrifice’ (meaning killing). I suspect of course that it would not be good PR at present to make too much of these practices. For the rest of us, what we should be doing is re-instating the prayers of ‘Grace’. Most Pagans dislike and avoid these prayers as a result of distaste for their Christian versions. But it is proper to Hallow our meal, to Make it Sacred, whatever it might consist of, including wheat and lentils, to give thanks for the Gifts of the Deities, for Life Given that ours may continue. (In due course, the worms will have us.)

In modern English usage, the word ‘sacrifice’, with the meanings of either killing as propitiation to a deity, dates from late 13th century ce. Usage in the sense of ‘giving up something’ is more recent (1590’s). The original Latin word ‘sacrificium’ or ‘sacrificus’ had the meaning of ‘performing priestly functions’, so was in no way limited to killing animals. If you are more learned in Classical languages than myself, you will be aware that many ancient words are translated just by ‘sacrifice’. I have argued above that the whole notion of killing-as -propitiation is not just nasty, but fundamentally theologically invalid, and in fact, not actually ‘sacrifice’ as exemplified by myth. Further to that, the entire notion in modern usage is a specious hodgepodge – to use the word at all is only to confuse and be confused.

In a subsequent blog post I intend to discuss the ideas still adhering to ‘sacrifice’ in modern Paganism and think further, not just in simple ‘rejection’ but as to a different way of thinking our relationship to all the kindreds of Spirit.