A story as the Mabinogion might have been…

My story is of long past. Though nowadays we can know of Annwm only through the journey of shaman-trance, in that time the Shining Ones, and those favoured among mortals, could move freely between the worlds.

At the beginning of my tale, Pryderi was Prince of Dyfed. Indeed, it was said that he was Son of a Goddess, that his mother Rhiannon had taken mortal form to wed his father Pwyll. Be that as it may, he was the finest of kings, a man of great strength, and a fearsome warrior. For he had fought with Bran the Blessed in the great war against Matholwch. Of all those who had crossed the sea, Pryderi was one of only seven returned. He was no longer a young man, indeed he was somewhat older than he looked, for many years had he spent in the enchanted assembly that feasted with the Noble Head of Bran.

Pryderi had pledged to Cigfa, Sovereign Priestess of the land – she was one of twelve Wise Women who together held the power of the great stones of Preseli. They had a son, called Gwri, for his golden hair (as was his father’s long before) and a daughter named Yssa. As this tale begins Gwri was just coming into manhood, whiskers on his chin but soft still, and Yssa a maid of but nine summers. Pryderi took life quite easy, for the Twelve made decisions on all that mattered, and Pryderi thought his fighting days well done with. Since first he could speak, Gwri had loved Goewyn ferch Pebin, who was daughter of another of the Twelve (indeed the two had been born on the same day, nine months after a well-celebrated festival). Goewyn was called fairest of all the maidens that were known in her time. To but look at these two brought lightness to the saddest in heart.

To the north of Dyfed is the land of Gwynedd. There Math ap Mathonwy was lord. Many said Math was himself of the Shining Ones, and that he was brother to Dôn, Goddess of the Great River, though She did not dwell among mortals. Math was now of great age in mortal body, yet thought to hold much of secret wisdom. Math’s heir was Gwydion, called Child of Dôn (though none knew of his fathering). But Gwydion thought only of power for himself, and twisted his uncle’s teaching in cruel sorcery.

Gwydion lusted after the sweetness of Dyfed, for much of Gwynedd was mountain harsh and cold, and he tired of the taste of mutton stew and barley-bread. One day, he said to his uncle

“Lord, I hear much told of the toothsome meat of Dyfed. I would take me some men and see what we might rustle.”

Now in those days it was not unusual for the young men of a tribe to make such raids, and rarely was much blood spilt, so Math gave his assent to Gwydion’s request.

Gwydion made journey to the court of Pryderi at Rhuddlan Teifi, accompanied by eleven picked warriors. Blades they kept hidden and all dressed as bards. Nearby to the court, Gwydion picked up some stones and leaves and vines of ivy, and by illusion of magic made these look like wonderful harness of gold and jewels. He knew not yet what his plot should be, thinking folk easily seduced by glitter.

Pryderi welcomed these ‘bards’ to his court and called feast for them. Gwydion made much show of his golden gifts, and though the men had but little merit, Gwydion made up for all, smooth in tale and almost sickly in the sweetness of his voice. His performance completed, Gwydion praised the plenty of Dyfed, and spoke of the Blessed Twelve, saying

“Lord, I would ask that you might send some of the Holy Women of Dyfed to Gwynedd with me, to guide and aid us there, for our land is sour compared with yours.”

But Cigfa spoke quietly into Pryderi’s ear, saying

“Get this man and his hangers-on from our court as quick as may be, my husband. I have looked into his eyes and therein I find no soul, but rather a seething mass of poison.”

Pryderi made after the way of princes, speaking much but saying little. He said to Gwydion:

“Prince of Bards, know you that the Holy Women of my land are not at my beck, but move as they do choose. Further though, you must know that they pledge a geis, each to serve the land until she has raised a daughter to succeed her. And if there are any that prefer the embraces of women, or otherwise choose not to bear children of their own body, still they will raise a fosterchild or one orphaned, to follow after.”

Gwydion laughed inwardly, thinking Pryderi much hen-pecked. But in his words Pryderi had given away a secret to Gwydion, for that falsest of bards had not before known of the girls. The feast was soon done with, but Gwydion made careful enquiry and easily learned that though the Twelve each held their own House, at this time the twelve young priestesses lived together, and that nearby. Eldest among them was Goewyn ferch Pebin, and youngest was Yssa ferch Cigfa. The plan of his treachery now seemed clear – the old sows might be troublesome, why not take the piglets?

And so, when all of the court were abed, Gwydion and his men went straight to the girls’ house. For sure the maids had a guardian gatekeeper, and she had been a warrior fearsome in her youth. But this night she was drowsy, and life was quickly choked out without her even seeing the killer. Sleepy maids are no match for strong warriors, and so the girls were all gagged and trussed within a minute. Each maid was tied to a warrior’s horse, and all set off hotfoot. Gwydion led his men away as secret as he knew, using his power of illusion to hide the trail so that grass seemed to grow back over hoofmark, and horses droppings no more than toadstools.

The house of Pryderi was quiet that next morning, many sleeping late after the feast, so it was not until mid-afternoon that Cigfa went to visit her daughter Yssa. Cigfa fell over the body of the gatekeeper, who was indeed her own mother’s Circle-sister. The honeycakes she had brought scattered on the floor. None slept after the first scream. The truth of things was clear enough, and Rhuddlan Teifi was fast in uproar. None even noticed that the golden jeweled harnesses had turned back to leaves and stones. Nor would they have cared.

Two of Pryderi’s fastest-riding heralds were despatched to Caer Dathyl, seat of Math, to pronounce ultimatum at this most unforgivable of injuries to the land of Dyfed. Pryderi’s captains were sent at speed to raise all twenty-one cantrefs of the south, in host of war without hesitation. Others of the Twelve came quickly to join Cigfa. All had tied sharp blades to their own girdles. Blessings and absolution each gave to their daughters’ fathers. Then Pryderi and his men rode forth, and the women held their land.

Meanwhile, Gwydion and his soldiers went as swift as they might with captives ahorse. Knowing they must be pursued, they journeyed around the east of the mountains, five days in all. Each night, the girls were treated most cruelly, so that the very flowers of the land shriveled in outrage. Coming at last to Creuwyron, close by Caer Dathyl, Gwydion had the girls thrown into a pigsty, locked fast against escape, but perhaps they felt safer therein, at least no further molested.

Moving quickly to Caer Dathyl he found all in readiness for war.

“It is amazing how slowly you have come” he was told.

Math had raised himself from his dreaming, and was ready for battle, yet he held aloof from other men. He bore the magic club, which could kill nine men with one blow. But then Math said to Gwydion:

“Where are the animals you went for?”

With this, Gwydion realised that Math did not yet know truly of what had been done. And Gwydion but replied:

“They are penned in the cantref below us”.

For though the heralds of Pryderi had come and gone, their message had been delivered to Gilvaethwy, that was the younger brother of Gwydion, acting as castellan. Maintained in luxury at Caer Dathyl he was good for nothing but lies. Gilvaethwy envied this great coup by his brother. Indeed he hoped that the aged Math might be slain in fighting and so had said only that the war was in consequence of Gwydion’s pig-rustling.

Soon the trumpets were heard and battle was joined and though they had greater numbers, the men of Dyfed perhaps fought more in rage and anger than with care, and so did not take victory. Two days they fought with slaughter on either side. After the second day, Gwri and twenty-three young men and noble boys of Dyfed came before Pryderi and Gwri said:

“Lord, we understand that you would not allow us to fight, young as we are and untried in war. Yet nought has come of battle, and the holy maidens are still captive. And so we ask, we that are their brothers and lovers, that we may be given as hostages instead of the girls. Two of us for each of them. And even if this be our own death, just as you would without hesitation give your life for the safety of the holy ones, let that be remembered of us.”

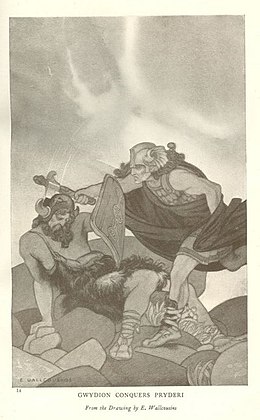

Pryderi’s eyes were wont to weep at this, but could find no word to stay his son so steadfast of courage, that he gave his assent, and so the boys were taken by Gwynedd. Yet Gwydion fab Dôn was ever faithless and in the pigsty the maidens remained. Insulted further so, the men of Dyfed fought again still greater enraged and reckless, and more of them died, until at last Pryderi challenged Gwydion to single combat, sending message to Math:

“Let him who has wronged me put his body alone against mine.”

And in that sad battle, as others have told, by magic and enchantment, it was Gwydion that prevailed and Pryderi that died. The men of Dyfed raised a great mound over their king’s body. After that, those nobles of Dyfed that still lived were brought before before Math who said to them:

“Men of Dyfed, that there be no more war between us, I release to you your own young lord and his brothers that were given in truce”.

The eldest remaining of Dyfed was about to speak when quickly were Gwri and the twenty-three boys brought also before Math. You may be sure that in his imagination Gwri saw himself to leap upon Gwydion, standing there at the side of Math, even with no weapon other than his own teeth. But the weight of his new and unsought kingship was upon him, and so he said straightway:

“Lord of Gwynedd, that men call Math the Wise, know you that we twenty-four were taken as hostage against release of the twelve holy maidens of Dyfed. Yet still they are held in the filth of yonder pigsty.”

Math was aghast to know of this falseness done in his name, but Gwydion, fearing his wrath, said quickly,

“Let the little pigchaser take his piglets and begone”.

Although imprisoned, the girls were told everything that had happened, and so were ready when the pigsty gate was smashed down. Goewyn led them forth, barefooted were all in mud, yet in procession they walked as if in sacred festival, with the youngest flanked by older ones. The men of Dyfed gasped, for the girls’ shifts were ripped and bloodstained, and they had each but a filthy horse blanket around their shoulders for warmth and decency. Much of Goewyn’s face was blue as a warrior’s tattoos, and the others were but little less marked. Goewyn’s eyes were a raging fire, and some said they saw snakes seething in her hair, readying to strike. Straight she strode the few steps to face Gwydion. She raised her left arm, two fingers outstretched and did not hesitate to speak.

“You, Gwydion fab Dôn, you alone are the cause of all this blood and pain. You thought to take the Power of Dyfed from us that are our mothers’ heirs. You wrought foul rape upon me and upon my holy sisters. even upon the little maids too young for monthly flow. Dishonour eternal you have brought upon your Lord and the land of Gwynedd. We are not broken by your outrage. You laughed as we bit and clawed at you, yet our power is not in body but of our land herself. The sacred waters of the Mothers will wash your filth from us and we shall be renewed.”

“I curse you, Gwydion fab Dôn, that none born of woman shall ever again come willingly to your bed. Your death I see, in pain, awash with blood and filth, nor shall Mother Earth receive your bones.”

Goewyn stopped but to draw breath, and all was silent. Some of the men had fallen to the ground and thrown cloaks over their heads, fearsome of what further curses Goewyn might yet speak. But Gwydion fab Dôn raised his great heavy-gloved fist and struck the girl hard across the face, and she fell to the ground. With sneering glance, Gwydion turned on heel and stomped away, followed quickly by his soldiers.

It was but the briefest of moments before Gwri was at Goewyn’s side, for he was indeed her own true and steadfast lover. And if she was heard to whimper now a little, and clutched at him very tightly, none thought the less of their priestess. The Raging One was gone. Soon as might be, biting hard on her lip, she pulled herself upright against Gwri and straight they went to comfort little Yssa and the other maids. No longer was there need to be brave, nor was Yssa the only one whose father had died, and tears could no more be held unshed.

Gwri, lord of of Dyfed, led his people back to their homes. After crossing the river Dyfi, they burnt all its bridges, having no wish for more of Gwynedd. The Twelve came from their Stones to bathe each of their daughters in seven sacred pools, and laughter was heard again in the house of the maids, though they did not forget. A year onward, Goewyn led the people in the Rite of Remembrance for Pryderi and for all of the dead. Thus healed of bruises to body and soul, Goewyn pledged troth with Gwri and took place at his side as Queen.

For many years their land rested in plenty and in peace, for so ashamed was Math of the deeds done in his name that he forbade absolutely that any blade or arms again be taken abroad. It was said that in all those years, no girl or woman in Dyfed was ever laid with against her own will, and indeed folk were perhaps as happy as possible for humankind. Each of the twelve maids in due course succeeded to her own mother’s place, and raised another daughter or fosterling to follow after.

Yet there is more still to this story. Gwri was fortunate to keep his fine head of hair, though the gold had become but a few threads in the silver, and that of Goewyn likewise. Gwri took no interest in luxury, though constant in his hospitality. At planting-time and at harvest-time he worked in field as long as any, and was steadfast to all in need. It was Gwri’s custom to make circuit of the land, so as to resolve the minor problems and disputes that always arise. In ought more serious, always was he guided by the Twelve.

There came a day when Gwri was to set out and Goewyn came to bless him farewell. She laughed at his plain clothing, saying

“If you would look like a pigman, my love, wear you the sword today, that you might be known as king. I have heard too, that wild dogs are preying the hills, danger for a man unarmed and alone.”

And so she girded him with the sword of Pryderi, his father. Gwri traveled a few days about the land, and into the hill places where more sheep dwell than people. Then, skirting about a great rock he saw ahead of him a ford, where a horse stood drinking and its rider knelt in the water.

Gwri’s sight dissolved into a red mist, and in his mind’s eye he was a great falcon, high in the sky, with a black crow below. The voices of women spoke clearly to him.

“This is the moment you have long waited.”

“Into your talons he is delivered.”

“Strike in all your strength and ours with you.”

The heart of Falcon-Gwri speeded beat now ten times a second, and wings folded into stoop unstoppable – the Man-Gwri, known before as so gentle a rider, hard spurred his horse that lifted hoof into full gallop. As the talons of Falcon-Gwri stretched out so Gwri the King drew sword from scabbard and raised it high. And as Falcon-Gwri hit crow in an explosion of feathers and blood, so fell the sword of Gwri the Constant into the man as he was just rising and turning to face this unexpected rider.

Now Gwri had indeed only ever raised wooden sword against stuffed dummies, and in all his days had taken neither edge nor point to any. So his strike was less expert than some would have made, and the man before him still breathed it seemed. The blow was truly grievous; ribcage was smashed and blood bubbled from the open lung within. Belly was cut deep and its soft organs pierced. At its last the swordblow had slashed the man’s breeches and left him in nakedness.

Gasping and dribbling much blood, the man said

“Have mercy, kind lord. Who art thou, so cruel to harmless traveler?”

But Gwri dismounted from his horse, stood away from him and said

“I know you, Gwydion fab Dôn. I am Gwri, who you called Pigchaser. Now at last are avenged fair Goewyn and her Holy Sisters, and the sword of my father Pryderi may rest.”

Gwydion then rolled onto his back, saying slowly:

“Have mercy then lord and give me clean death from this mess of guts and blood”.

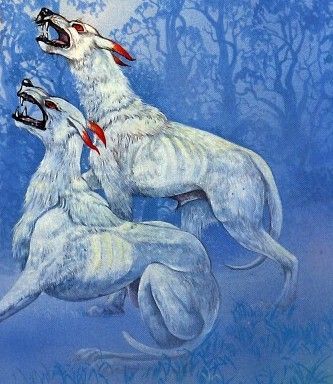

Gwri heard a howling, and saw close by a pack of some twelve wild dogs, drawn by the smell of blood, all a-slavering. Great hounds they were, as tall at shoulder as a roebuck. White of hide they were, but with ears of red, Gwri quickly took tether, bridle and saddle from Gwydion’s horse, and slapped it hard, to run quick from the dogs. Mounting then his own mare, that was quiet now despite the nearness of those creatures, he moved a little further from the ford. So the dogs moved closer, and Gwri said:

“I know of your foul magic Gwydion fab Dôn, that if you can but see the eyes of him who strikes you, then you can suck that man’s own life energy through the very sword, thereby to renew yourself and ruin your assailant. Only thus could you defeat great Pryderi, who fought alongside Bran the Blessed and yet lived. So I will not strike you again, and in blood and pain you will die as Goewyn foretold. The Dogs of the Destroyer will rend your flesh. You will have mercy of them and not scream for long, I think. For though they may start with the tenderest parts, soon their teeth will rip at your throat.”

Gwri the Constant then turned his mare’s nose to homewards, thinking that now the long-borne geis was done, and perhaps this was the time for his and Goewyn’s own golden-haired son to take oath before the Twelve and take up the kingship.

And so it was that Gwydion fab Dôn was brought to naught, and never did he become King in Gwynedd. The dogs were hungry and did not hesitate to crunch bones once tenderer meat was done with. So as Goewyn had cursed, Mother Earth received him not, and of the Great Wizard of Gwynedd nothing remained but the droppings of dogs.

If you came to this story directly, my ‘explanation’ is here :

https://pandorasjar.org/pryderi-and-the-pigs